News & Views Special Edition: How much scholarly publishing is affected by US Presidential Executive Orders?

Overview

Following the 2024 US election, the new US administration has instructed employees in some key federal agencies to retract publications arising from federally funded research. This is to allow representatives of the administration to review the language used, to ensure it is consistent with the administration’s political ideology. In this special edition of News & Views, we quantify how many papers might be affected and estimate their share of scholarly publishers’ output. The initial numbers may be small, but we suggest the effects on scholarly publishing could be profound.

Background

On 20 January 2025, Donald J. Trump took office as the 47th President of the United States. Within hours he signed an Executive Order1 (EO) 14168 proclaiming that the US government would only recognize two sexes, and ending diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs inside federal agencies. The following day, his administration instructed federal health agencies to pause all external communications – “such as health advisories, weekly scientific reports, updates to websites and social media posts” – pending their review by presidential appointees. These instructions were delivered to staff at agencies inside the Department of Health and Human Services (DHSS), including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The events that followed are important, as they directly affect scholarly papers and our analysis.

A memo on 29 January instructed agencies to “end all agency programs that … promote or reflect gender ideology” as defined in the EO. Department heads were instructed to immediately review and terminate any “programs, contracts, and grants” that “promote or inculcate gender ideology.” Among other things, they were to remove any public-facing documents or policies that are trans-affirming and replace the term “gender” with “sex” on official documents.

By the start of February, more than 8000 web pages across more than a dozen US government websites were taken down. These included over 3000 pages from the CDC (including 1000 research articles filed under preventing chronic disease, STD treatment guidelines, information about Alzheimer’s warning signs, overdose prevention training, and vaccine guidelines for pregnancy). Other departments affected included the FDA (some clinical trials), the Office of Scientific and Technical Information (the OSTP, removing papers in optics, chemistry and experimental medicine), the Health Resources and Services Administration (covering care for women with opioid addictions, and an FAQ about the Mpox vaccine).

Around this time, it further emerged that CDC staff were sent an email directing them to withdraw manuscripts that had been accepted, but not yet published, that did not comply with the EO. Agency staff members were given a list of about 20 forbidden terms, including gender, transgender, pregnant person, pregnant people, LGBT, transsexual, nonbinary, assigned male at birth, assigned female at birth, biologically male, biologically female, and he/she/they/them. All references to DEI and inclusion are also to be removed.

The effects of the EO

Commenting on the merits of policy and ideology lies beyond our remit. However, when these matters affect the scholarly record – as they clearly do here – then they are of interest for our analyses. Specifically, what might the effects of the EO be on the publication of papers, and what effects might accrue from withdrawal of research funding?

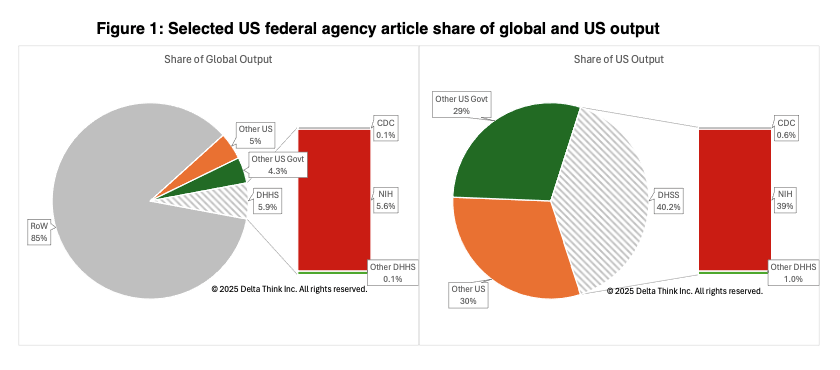

If federal agencies are being instructed to withhold or withdraw submissions, then, to quantify what this might mean to publishers, we have estimated the volume of output from a few key federal agencies. It is summarized in the following chart.

Sources: OpenAlex, Research Organization Registry (ROR), Delta Think analysis.

The charts above show the output funded by a few key US federal agencies as a share of global output (left) and US output (right).

- The data span the previous 5 years.

- The US accounted for around 15% of global output.

- The CDC accounted for a tiny share: 0.1% of global output and 0.6% of US output.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), of which the CDC is a part, accounted for just under 6% of global output, but just over 40% of US output.

- The NIH produces around 95% of DHHS output.

- Note, that these samples are based on OpenAlex data, where papers are indicated to have the funders as classified above, or by one of their subsidiaries (as best we can estimate).

The proportion of CDC-authored papers is tiny, and so their suppression is unlikely to lead to a drop in publishing output. However, should the orders spread to other areas of health research, then the effects could be profound – especially for journals and publishers relying heavily on US-authored papers. As we saw in our last market sizing update, significant authors moving away from publishing venues can have profound effects on publishers’ output and revenues.

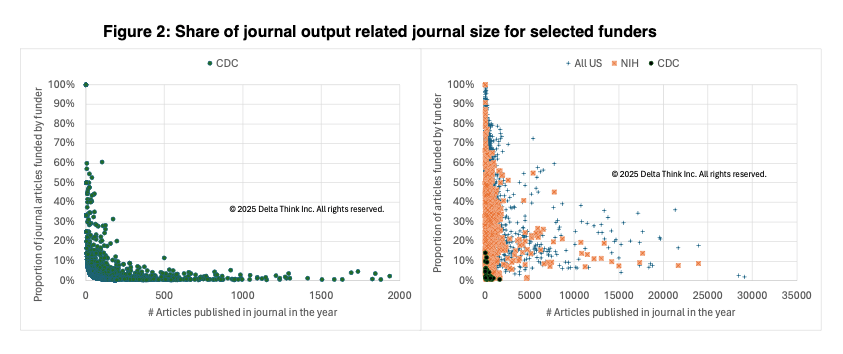

As ever, the averages are unevenly distributed, so we looked at how individual journals might be affected.

Sources: OpenAlex, Research Organization Registry (ROR), Delta Think analysis.

The charts above show the impact of funding on individual journals. They show the share of journal output attributable to some key funders, relating it to overall size of the journal. Each point represents one journal.

The left-hand chart focuses on papers arising from CDC-funded research.

- On average, only 5% of papers in journals are attributable to CDC-funded research.

- However, the chart’s sample is small. Only 10% of journals receive these submissions.

- Where the CDC affects a larger share of papers, the journals tend to be small.

- For larger journals, the CDC accounts for smaller shares of output.

- A very few journals are heavily reliant on CDC-funded research. (The outlying journals at 100% published just the CDC paper that year; they could either be CDC journals, or a shortcoming in the underlying data.)

The right-hand chart puts the CDC figures in context.

- It compares the CDC (green dots, clustered bottom left) with all the NIH (orange crosses, which includes the CDC) and all US-funded papers (blue plus signs). The point of the charts is to show the overall patterns, not to highlight details of specific journals.

- To keep the data manageable, it shows only journals with more than 0.5% of their papers funded by the funders in question. We can therefore focus on journals that may have a significant proportion of papers affected.

- The small cluster of dark green CDC dots bottom left shows how small the numbers of journals with CDC-funded submissions are relative to the wider market.

- The NIH and US federal agencies can account for significant proportions of journal output for even modestly sized journals, across many more journals. Many journals are wholly reliant on papers from these funders.

So, while a few journals may be affected by CDC submissions, and a very few of those significantly so, the effects are mostly small. Only a few percent of journals would see any significant drop in their overall submissions due to the suppression of CDC papers.

Conclusion

It’s not unheard of for an incoming US administration to ask for a pause to review information before it’s publicly released. However, the scope of the current orders appears to be unusually broad and aggressive. There were no similar restrictions on communications issued at the beginning of the last two administrations.

From one perspective, the effects of the orders to the CDC are small. They affect a relatively small volume of papers, which will not make much difference to most journals. If like-for-like language can be found that doesn’t affect the science, then the issues blocking the papers may be fixed easily.

However, grants are being withheld and reviewed across the much larger agencies such as the NIH and NSF. Even if orders are later rescinded, or moves reversed, their chilling effect is already taking hold. Pauses in funding may disrupt a project’s cashflow, causing it to shut down even if the funding is later reinstated. It already appears that there could be a significant drop in funding for future research, and the NSF is vetting existing projects. Some publishers are already witnessing a drop in submissions. As the footprint of reduced funding increases, we may see a much greater drop in submissions.

We have examined the effects of submissions here, as they are directly under the control of federal agencies. But, as a further EO (14173) explicitly targets the private sector, might publishers be sanctioned for publishing unacceptable papers?

We are on a journey, as the new administration pushes ahead and worries about course correction later. En route to whatever the steady state is, publishers may be required to make a choice between the fantasy of the ideology and the reality of the science. E pur si muove.2

1 "Executive Orders (EOs) are official documents … through which the President of the United States manages the operations of the Federal Government.” The directives cite the President’s authority under the Constitution and statute (sometimes specified). EOs are published in the Federal Register, and they may be revoked by the President at any time. Although executive orders have historically related to routine administrative matters and the internal operations of federal agencies, recent Presidents have used Executive Orders more broadly to carry out policies and programs." – US Bureau of Justice Assistance, part of the US Department of Justice. Refer to the US Federal Register for a full list.

2 "And yet it moves" is attributed to Galileo Galilei after he was forced to recant his statements that the Earth moves around the Sun rather than the other way around.

This article is © 2025 Delta Think, Inc. It is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. Please do get in touch if you want to use it in other contexts – we’re usually pretty accommodating.