News and Views: How much content can AI legally exploit?

This month’s topic: How much content can AI legally exploit? Scroll down to read about this topic, along with the latest headlines and announcements. Delta Think publishes this News & Views mailing in conjunction with its Data & Analytics Tool.

Please forward News & Views to colleagues and friends, who can register to receive News & Views for free each month.

Delta Think will be attending several upcoming conferences, including APE (Jan 14-15), NISO Plus (Feb 10-12), and Researcher to Reader (Feb 20-21). We would love to see you there – please get in touch or visit our Events page to see all the meetings we will be attending.

How much content can AI legally exploit?

Overview

During the recent PubsTech conference, we were asked how much content could be legitimately used to train artificial intelligence systems without being specifically secured through a licensing agreement. In considering this question, we find some counterintuitive results.

Background

Generative AI (genAI) is a type of artificial intelligence that can create new content—text, images, music, and more – by analyzing patterns in massive datasets. These models are typically trained on publicly available data scraped from the web. In the US, developers often invoke the “Fair Use” copyright doctrine to justify this training, claiming it is limited to specific purposes (training) and transformative in nature (different from the original use).

In reality, the legal position is complex and evolving, with many rights holders and their representatives – unsurprisingly – taking the opposite view. Even if legal clarity emerges, different geographies and jurisdictions will likely reach different conclusions.

The legal complexities of AI and copyright law are beyond our scope. However, for scholarly publishers, particular issues apply. Half of our output is open access, and open access content is designed to be reusable. Open or not, content has varying restrictions on onward use – for example, non-commercial use is often allowed with attribution.

How much scholarly content is exploitable?

For the purposes of analysis, we will assume that the license under which content is published will have a material bearing on the legitimacy of its use to train AI systems. Therefore, looking at share of licenses, we might be able to answer our question.

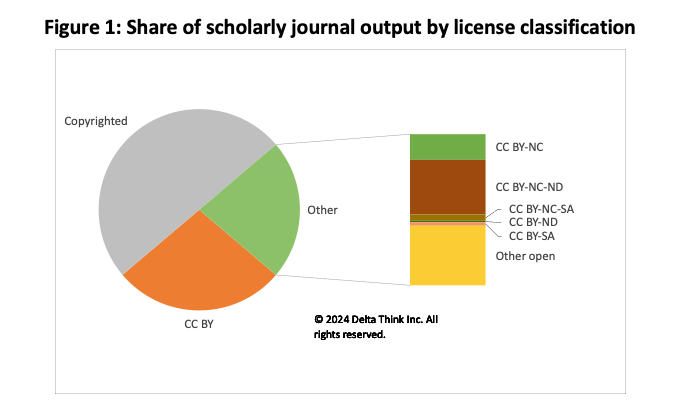

Sources: OpenAlex, Delta Think analysis.

The chart above shows the share of total scholarly journals output in 2023 attributable to various license types:

- Just under 50% has no open license or has no license specified. We deem this to be copyrighted content, with rights resting with the publisher. This includes public access (aka Bronze OA) output which, although available outside a paywall, does not have onward usage rights.

- Just under 28% is Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY). This allows unrestricted reuse if the work is attributed as specified by the licensor. It is the license often mandated by OA advocates.

- The remaining 22% has more restricted Creative Commons licenses. As well as requiring attribution, these licenses impose further limits, such as in commercial use (13%), or use in derivative products (9%).

Only tiny amounts of content have no restrictions at all (e.g. CC0), or other restrictions (such as “Share Alike” licenses). The bulk of our analysis is covered by the items listed above.

The Open Access Paradox

Open access was envisioned as a way to make scholarly content more portable and adaptable in the digital age. Yet, its application in AI training faces practical challenges.

Most OA licenses, even permissive ones like CC BY, require attribution. However, generative AI models inherently strip attribution from the data they process, making compliance nearly impossible. Specialist AIs might be trained to circumvent this, but the bulk of big-name gen AI tools don’t. Compliance with the most basic OA requirement of attribution is unworkable.

Additionally, while traditional licenses clearly delineate permissible use, OA licenses often depend on interpretations of “non-commercial” or “derivative” use that may vary by jurisdiction.

In contrast, traditional copyright-protected works – often controlled by publishers – can be directly licensed for AI use. Publishers and AI companies are already striking deals, bypassing the complexities of OA compliance.

Conclusion

The claim of legitimate fair use in the context of AI is to be determined by the courts and legislators. Definitions and exemptions will vary between jurisdictions. For example, the UK has a much narrower definition of “fair dealing” than the US’s fair use, allowing text and data mining under certain conditions. The EU has no fair use doctrine in its copyright law; its nascent AI Act instead looks at requirements for transparency, accountability, and data governance. Further, even where the training of systems may be allowed, the application of the results might be infringing. (An analogy is the difference between making fake money for a movie and trying to buy a car with it.)

Whatever the legal details, can AI companies simply license content from publishers?

For copyrighted content where the publisher holds the copyright, yes. Reuse is in the gift of the license holder, and licensing deals are an established part of publishing. Scholarly publishers are now licensing content to tech companies. Once agreed, the licensee can push on with the agreed use. The only challenge here is one of optics, in cases where authors do not support their work being used to train AI.

But the rise of generative AI exposes a digital irony: the very openness that defines open access may hinder its use in one of the most transformative technologies of our time. Meanwhile, traditional “closed” licensing remains a smoother path for AI developers, albeit at a cost. The challenge for publishers and authors is to navigate this paradox, ensuring their work is both protected and impactful in the AI-driven future.